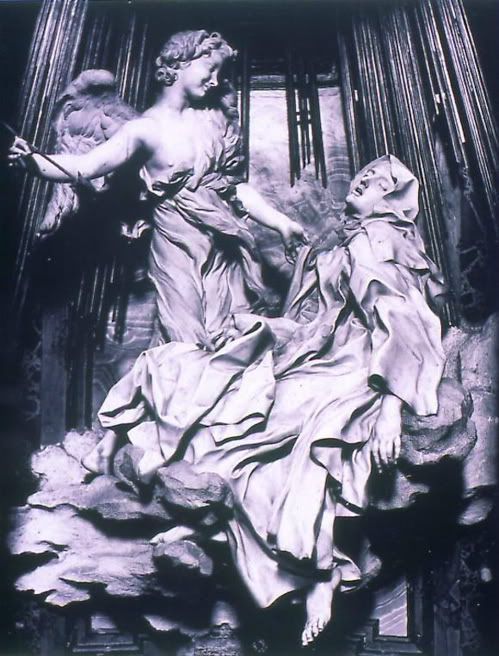

"Bernini's Ecstasy of St. Theresa (1647-52), it hardly needs saying, is no middle-aged nun rising up the wall in her habit like an untethered balloon, nuns clinging to the hem. This woman is unforgettably beautiful, a match for the beaming seraph. They are, in their way, a couple. We see his exposed breast, infer hers. How could Bernini make visible the tide of ardent feeling washing through Theresa? Here he has the crucial conceptual insight of the entire drama.

He turns her body inside-out so that her covering, her habit, the symbol of chastity and containment, the symbol of her discipline - becomes a representation of what's going on inside her. It's the accomplice of her helpless dissolution into a liquid bliss.

It is, in fact, the climactic shudder itself, a storm surge of churning sensation, cresting and falling as if the marble had been molten. And these billows pour themselves from the smiling angel directly into Teresa's robe, where they join an ocean of heaving waves that folds into hollows and crevices, like surf breaking on a shore.

There's nothing furtive about any of this. Bernini wants us to look and look hard.

Why is this his greatest masterpiece? Because he's managed to make visible, tangible actually, something we all, if we're honest, know we hunger for, but before which we're properly tongue-tied. Something which has produced more bad writing, more excruciating poems than anything else you can think of.

No wonder, when art historians look at this, they tie themselves in knots to avoid saying the obvious. That we're looking at the most intense, convulsive drama of the body that any of us experience between birth and death. Which is not to say that what we're looking at is just a spasm of erotic chemistry. It's precisely because it isn't just that. Because it is somehow a fusion of physical craving and, choose your word, spiritual or emotional transcendence, that Bernini's Ecstasy of Saint Theresa is a sculpture that possesses the beholder completely, the longer we stare.

So perhaps when that 18th-century French connoisseur said, "If that's divine love, I know it well," he wasn't making a sly joke at all, but doffing his hat to Bernini for using the power of art to make the most difficult, the most desirable thing in the world: the visualization of pure bliss."

© Simon Schama, 2006